Infection is the most common cause of death in newborns, causing at least 2.6 million infant deaths per year. Even though the majority of newborn deaths occur in resource-poor countries, neonatal morbidity and mortality is also a significant problem in resource-rich countries. For instance, in Canada, 75% of infant deaths under 1 year occur during this critical newborn stage. Our group is working to understand why newborns are so prone to infections and the pathogens at play, so that we can develop effective interventions and preventions against diseases.

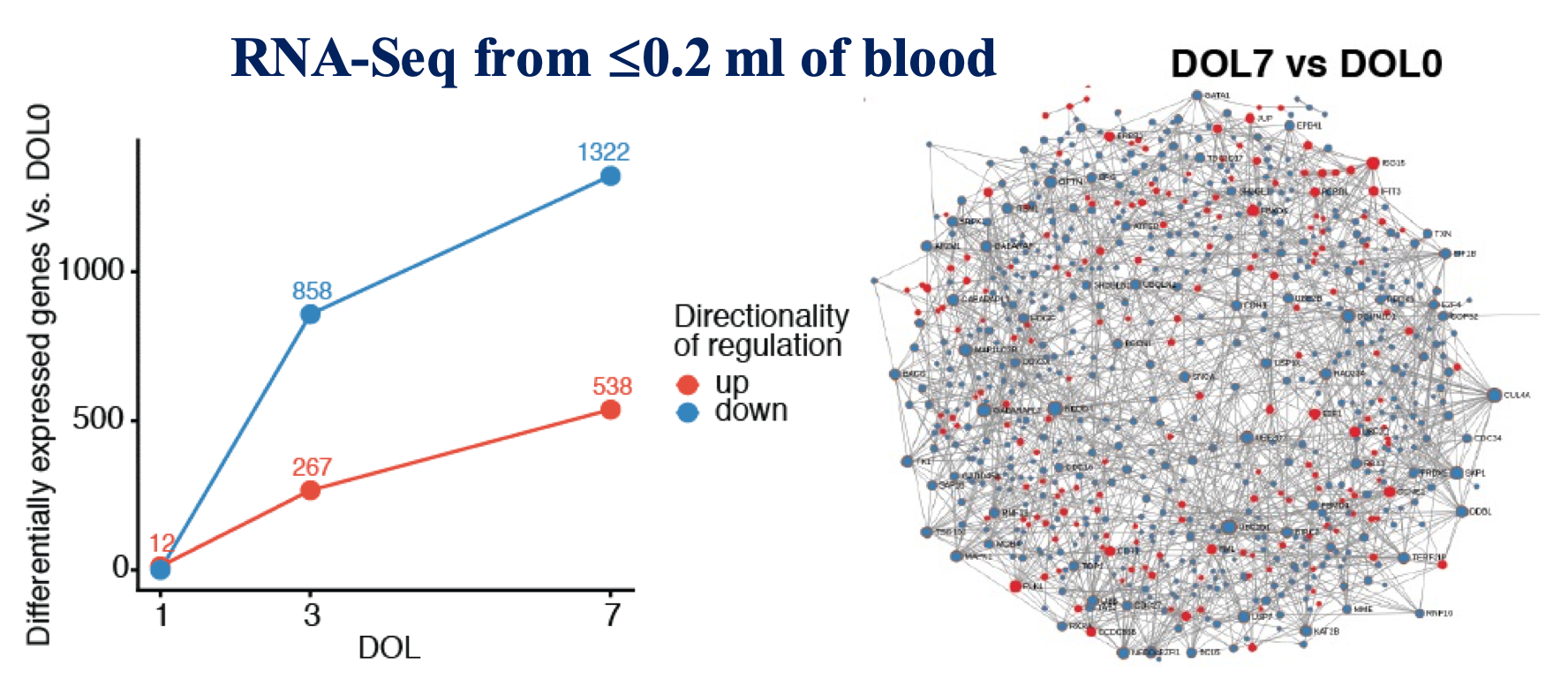

The transition from the sheltered in-utero environment to the microbe-laden outside world requires a dynamic reprogramming of the neonatal immune system, shifting from “quiescent” mode to responding rapidly to microbial and environmental stimuli. However, the molecular details of newborn immune system development during this critical period are poorly understood. Our recent work, published in Nature Communications as part of the NIH-funded Human Immunology Project Consortium (HIPC) EPIC project, began to tackle this problem by revealing that newborn immunity, rather than being simply immature as previously thought, actually follows an exquisite, consistent and detailed developmental trajectory that most likely reflects adaptation to the distinct demands of early life (Figure 1).

This work provides a baseline to further study what happens when deviation such as infection and neonatal sepsis occurs. Sepsis is triggered by microbial infections and/or major trauma, which leads to a dysregulated host response causing life-threatening organ dysfunction. Together with our clinical partners from around the world, we use machine-learning approaches to analyze blood transcriptomics from neonates to identify potential gene signatures of sepsis.